Security Testing

Tomaso Vasella

The 12th of May 2017, as well as the days that followed, will be remembered by a lot of system administrators across the globe. Within a day, a malware named WannaCry infected, according to various sources, 230.000 computers in far over 150 countries. Affected were not only end users, but also numerous corporate entities such as Deutsche Bahn or parts of the British National Health Service, short NHS. The incident didn’t only cause a massive media echo, but also lined the pockets of the crafty criminals behind it: Transactions to known bitcoin wallets show that a total of more than 125.000 US dollars in Bitcoin were paid to get rid of successful infections.

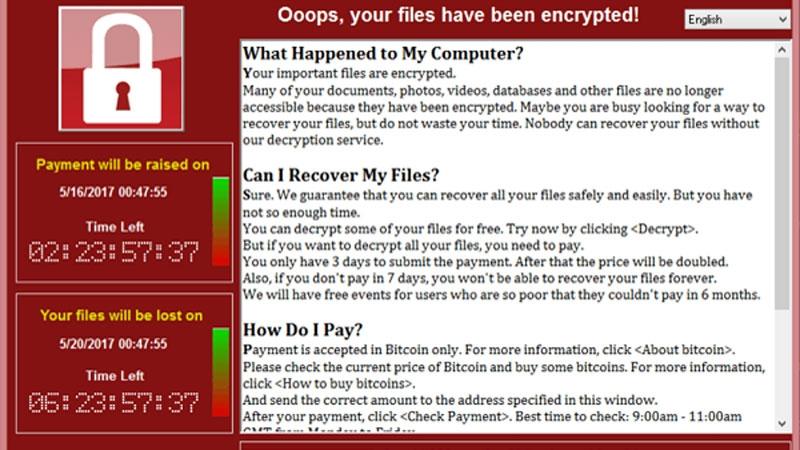

Ransomware is, in general, a far spread subgenre of malware, popularized mainly through the rise of cryptocurrency. The basic principle is very simple: A system will be infected and the malware will start to encrypt data using public key cryptography and to remove the original cleartext data. When the process has advanced sufficiently, the user will be informed, by a popup, that only paying a ransom – hence the name ransomware – will allow them to reclaim their data. The exact methodology varies: Some types leave it at the process described before, others apply more pressure to the user by irrevocably deleting single files at certain intervals until a payment is made.

The high spread of ransomware is clearly visible, also in the amount of letters and emails we get regarding that specific topic. It makes sense, since this type of malware has no intention of persistently hiding from the user. On the contrary, it announces its presence very proactively. Where badly patched machines of private users were, in the past, used as botnet zombies or mail relays infected with a plethora of malware, attackers are now able to make good money easily. The question we are being asked is simple and consistently the same: What do you do about ransomware?

As it is so often the case in information security, prevention is better than reaction: If you care about your data, you backup it regularly. This guideline should apply completely separated from the topic of ransomware. It is fairly common for users to forget that a broken, lost or stolen Macbook could, in its consequences, be very similar to a worst case ransomware infection. Further: A current patch level is essential to avoid a likely compromise without any interaction. In WannaCry, the attackers used the ETERNALBLUE exploit that recently got public exposure within the Shadowbroker leaks. The common advice given to users not to open emails is generally not wrong, but certainly not a sufficient preventive measure.

But what if an infection has already happened? What, if all good advice was ignored and the grim reality is that all the baby pictures, all the wedding videos and all the accounting information has been encrypted? Even though older ransomware variants had flaws that allowed decryption, newer variants use decent implementations of public key cryptography and are very careful to not let the private key ever touch the victim’s system before a payment has been received. Hence, here comes the big question: Should you pay?

The answer is, as ever so often, not so easy. Usually, we advise people – much like many other experts – not to pay ransom if it is, in any way, avoidable by restoring a backup or any other measures, even painful ones. We stick to that advice for various reasons: First of all: Nothing keeps a criminal from not decrypting your data, even when you paid up. It is technically feasible to create fake ransomware that just deletes data instead, though not very clever. Almost more importantly though: By paying, you finance the success and the evolution of malware and the professionalization of cybercrime.

But still: All of this is easy to say when it is not your data, that is at stake. And looking at the situation somewhat sober, paying is actually an option. During the last couple of years, sort of an “honour among thieves” attitude has been established among ransomware groups. Meaning: If you decide to pay, there is indeed a very good chance that you will be able to access your data again, even though there are no guarantees.

The process remains painful and expensive though: The ransom is usually around 300 to 600 Swiss Francs, to be paid in Bitcoin with certain time limitations. Even though the Swiss Federal Railway now sells bitcoin at a lot of their ticket machines, the process and the concept of cryptocurrency remain somewhat shrouded in mystery for layman.

But in conclusion: Yes, you can pay. It is a valid option and it will probably work. But it would better for all of us, if you would not and instead act now to avoid getting into a situation that requires you to pay and put your digital identity at the mercy of extortionists. For private users, that means: Stop postponing updates and start making backups. For corporations it’s a bit more complicated and it requires dealing with the challenges of managing legacy systems, patching cycles and hardening procedures. But nevertheless: Only those who prepare accordingly will be able to deal with the next, inevitable, wave of ransomware.

We are going to monitor the digital underground for you!

Tomaso Vasella

Eric Maurer

Marius Elmiger

Eric Maurer

Our experts will get in contact with you!