Human and AI Art

Marisa Tschopp

This is How we Interact with Machines

To investigate perceived human-AI relationships, we took the same approach Nass & colleagues have proposed years ago, based on the CASA paradigm , the tendency of humans to treat computers as social actors. In essence, you look at a theory of human-to-human interaction, in our case, how humans think about their relationship with other humans. You scribble out one human, insert conversational AI, and you can start working on your theory and gather data. We chose a theory that has received mighty empirical support in the past, about how humans think about their relationship with other humans, namely the relational models theory by Alan P. Fiske 1992. At the core, the theory states that ‘motivation, planning, production, comprehension, coordination, and evaluation of human social life may be based largely on combinations of four psychological models’ (Fiske, 1992).

Based on this rationale, we ask the following research questions:

Method: We conducted an online questionnaire study on Prolific with 367 participants and performed factor analyses (PCA, CFA) and analyzed how the participants perceived the human-AI relationship. We conducted a correlational analysis, including variables of system perception and user characteristics, where we looked at bivariate and partial correlations to better understand relational modes in the broader context of human-machine interaction.

Psychologists have looked at how humans form, build or end relationships with other humans from different perspectives. For instance, the role of proximity and frequency of contact, i.e. how close you live to each other or how often you see each other: Even the direction in which you open the door towards a neighbor may have an impact on how close your relationship will be to this neighbor. Others have looked at how much you integrate the other person into your understanding of yourself in order to define the relationship or measure psychological closeness. Psychological closeness is important for healthy relationships, no matter if we are talking about friendship or a romantic relationship.

Alan P. Fiske (1992) has proposed and received mighty empirical support for the relational models theory (Haslam & Fiske, 1996), even across cultures. In their theory, four modes of how humans think about their relationship with other humans are explained and can be measured quantitatively in a questionnaire: Communal Sharing, Equality Matching, Authority Ranking, and Market Pricing. The questionnaire contains various questions, referring to each of these dimensions to find out how participants think about a specific relationship (which they have to choose before answering the questions) and then rate their level of agreement on a scale from ‘not at all true’ to ‘very true’ for this particular relationship.

The four elementary forms of sociality

| Communal Sharing | Equality Matching | Authority Ranking | Market Pricing |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS is best compared to kinship-like relationships, where hierarchy does not matter and you do anything for the other person and expect nothing in return. This dimension can be measured with questions such as ‘The two of you are a unit: You belong together’. | EM recognizes a need for equality in terms of, if give you something and you expect something in return of the same value, so-called tit-for-tat. It’s best compared to roommates in a flat, for instance. This dimension is measured with questions such as ‘If you have work to do, you usually split it evenly’. | AR communicates that there is some form of hierarchy between the two humans. It is associated with words such as dominance, clear command-chains, just as in the military for instance. This dimension is measured with questions such as ‘One of you is the leader, the other loyally follows their will’. | MP is all about evaluating the costs and benefits of a relationship. Humans want something in return for their investment in the relationship, for instance, money as it is at work or in organisations people work in. This dimensions is measured with questions such as ‘What you get from this person is directly proportional to how much you give them’. |

To be able to investigate the perceived human-AI relationships through the relational models theory, we took the original questionnaire and adapted it to fit the context of conversational AI. We changed the wording and asked 15 people if they think the questions apply to the perceived human-AI relationships.

Much attention is brought to variables such as trust, to better understand its impact on how humans use (arguably complex) technology, such as AI or automated systems. Some even argue that trust is in fact a proxy for measuring relationships. Which makes sense, because according to the relational models theory, trust is critical in the communal sharing mode (keywords: Kinship, solidarity, in-group – basically asking: What do we have in common?), but it is thus only one part of describing a relationship. We argue that a multidimensional approach taken from the social sciences is promising, especially in the context of off-the-shelf conversational AI. Some other related work might be too narrow and not well applicable. For instance, empirical work on social presence. seems to lack depth as it does not allow for clear differentiation, e.g., how this social presence is characterized, and leaves open too much room for interpretation. Work in the human-machine interaction (HMI) field often has predefined roles, e.g., the robot as a friend or assistant, which does not apply well in the conversational AI context, where Alexa’s role is somewhat ambiguous. It could be an assistant-role as advertised, but might as well be perceived as a friend-role. In a nutshell, empirical, quantitative research focusing directly on the perceived relationship between humans and machines, from a multidimensional perspective, seems scarce (see. e.g., McLean & Osei-Frimpong, 2019). To fill this gap, we conducted this first study to better investigate human-AI relationships directly. We deemed this multidimensional approach very promising, especially as it has the potential to go beyond the traditionally dichotomous distinctions between emotional and rational dimensions of how humans perceive AI systems (see, for instance, Glikson & Woolley, 2020 for a detailed discussion).

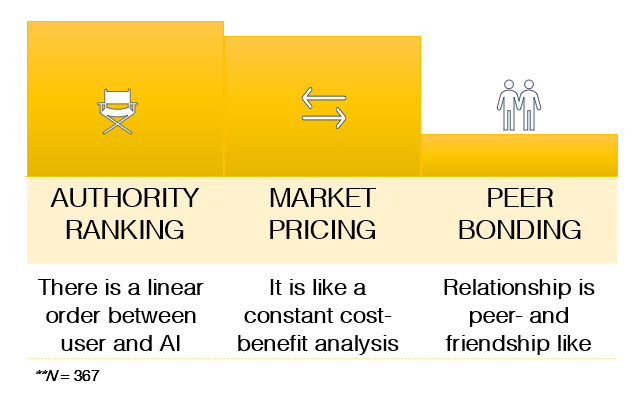

Our factor analysis revealed that the human-AI relationship was perceived along three dimensions. The original two dimensions of communal sharing and equality matching merged into one factor, we deemed rather emotional. We called this third factor peer bonding. Thus, the following three dimensions remained:

Looking deeper into the human-AI relationship modes, the results showed, that users mostly viewed their relationship as a hierarchical owner-assistant type (authority ranking). However, similarily many characterized their relationship as non-hierarchical exchange (market pricing). Only very few saw their AI as a peer or friendlike relationship. In other words, peer bonding was least pronounced in our data. This outcome already is quite interesting as it is enriching the dichotomous (rational-emotional) views dominating the HMI field.

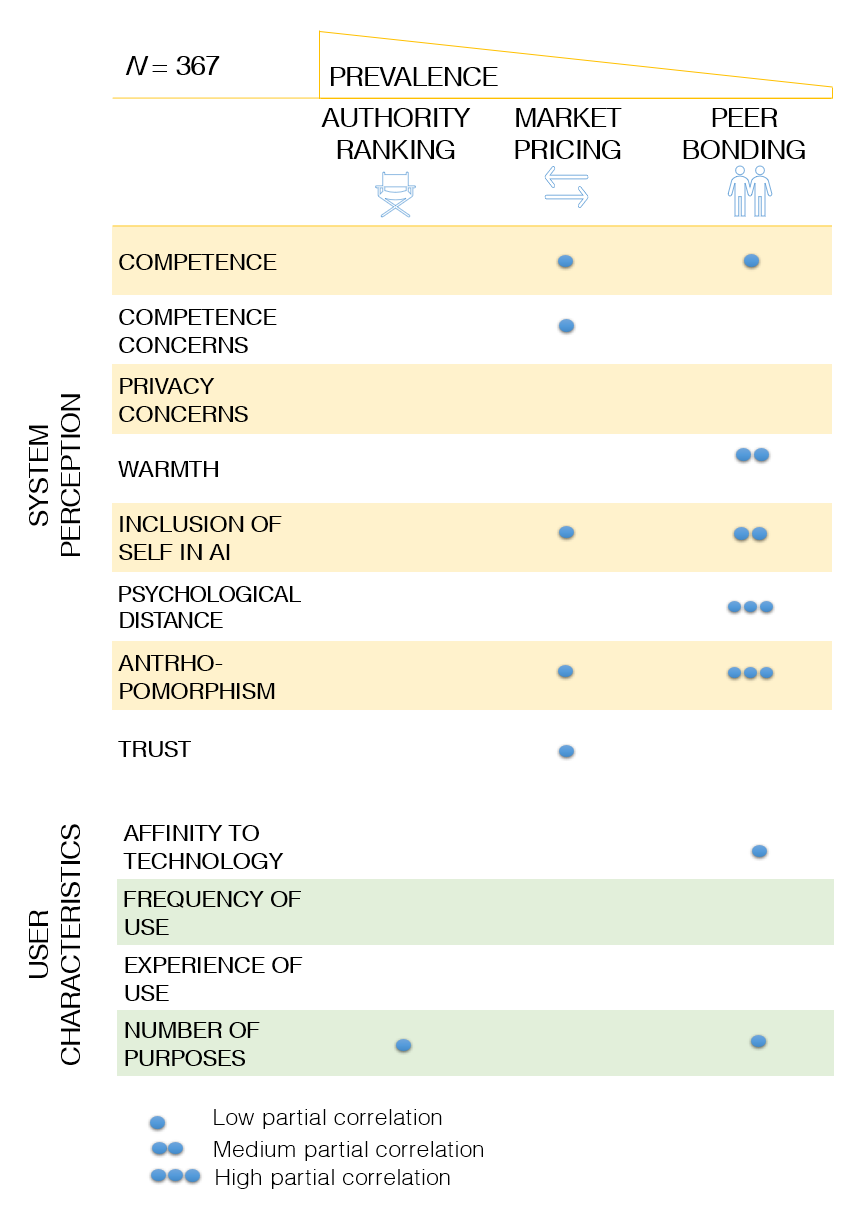

In order to see how the relational modes fit into the traditionally studied variables in the broader HMI context, we also measured various variables under the category of system perception and user characteristics. We conducted a partial correlational analysis and found that both market pricing and peer bonding showed interesting results in the bivariate and partial correlational analysis, rendering them more informative dimensions for future research. Surprisingly, the traditional assistant view offers no meaningful insights into system perception and user characteristics. Interestingly, peer bonding did not correlate with trust, whereas market pricing did, calling into question the emotional aspects of trust and supporting a rational account of trust in AI.

Of course, there are a number of limitations to this exploratory work. For instance, participants were mostly from the UK, hence we cannot make any assumptions across cultures. Furthermore, we did not measure how the relational models approach affects behavior. In other words, we cannot make any assumptions about the impact on user behavior. This is why we are now running the follow-up study, where we focus on a specific context, namely voice commerce. Voice commerce (or voice shopping) is when users make actual buying decisions via their digital assistant only. Thus, we want to explore whether the perceived human-AI relationships influence shopping behavior to make more concrete statements that may (or may not) be useful to investigate user behavior as well.

During the course of our research, we always want to keep in mind and critically reflect on the bird’s eye view in terms of consequences of our findings and the subject matter in general. Why are we doing this? Who benefits from it? Who could be harmed? How are results understood by designers? How do we communicate our research in practice? One of the bigger issues is around anthropomorphism (by design and by the user) and the potential to manipulate by design or users being exploited. As a matter of fact, conversational AI are pieces of hard- and software, connected to the internet and devices of our homes, powered by AI, which enables them to process human natural language quite well, and reply in a similar manner. Yet we seem to be unable to draw a clear line in order to perceive them as what they are: Just a tool. Humans’ capacity to humanize non-human beings is a blessing, as it helps us make better sense of the world. On the other side, it is also a curse, as it can be exploited so easily.

We hope that our work will contribute to a better understanding of the users of AI systems in order to make better decisions for the development, commercialization, regulation, and/or use of AI. We would like to raise the question of who benefits from a better understanding of the user? In addition to other stakeholders, such as regulators, who benefit from a better user understanding in order to protect them, the critical role of developers shall be addressed here. Obviously, developers benefit from a better user understanding to develop better systems, better interfaces, better conversations, etc.. But what makes a ‘good’ system? The EU has some great ideas in different areas, but it seems research is still tapping in the dark how much anthroporphism by design in which context is good.

The line between marketing and manipulation is not so obvious and we need to evluate whether the proposed relationship perspective may have to come with necessary normative caveats, similar to other streams of research: For instance, anthropomorphizing design strategies, are criticized for manipulating the user, which can lead to the user overestimating the capabilities of a system (Sætra, 2021). This can have undesirable behavioral consequences, like oversharing personal data (Aroyo et al., 2021) or overrelying on an automated vehicle (Frison et al., 2019). Particularly interesting may be that some studies have shown that respondents have expressed feelings of sadness or distress with regard to conversational agents, for instance, when asked to abandon the relationship (Xie & Pentina, 2022; Loveys et al., 2021). It is highly questionable how to deal with presumably unintended consequences, such as, when this relational attachment turns into an addiction.

Li, the co-founder of Xiaoice, Microsoft’s conversational agent with over 600 million users worldwide, confirmed the negative consequences, like addiction and sadness, in an interview for Hongkong Free Press (2021). However, he still believes that the benefits of this technology outweigh the risks. So the dilemma remains, where do we draw the line? With regards to our research, until we understand the fundamental theory and consequences of relationships between humans and conversational AI better, we advise refraining from applying the relational models theory repurposed for this study for design and marketing strategies.

Alexa, will you marry me? 6,000 times per day in India users propose to Alexa, Amazon’s digital assistant. Fortunately their love remains unreturned: We’re at pretty different places in our lives. Literally. I mean, you’re on Earth and I’m in the cloud. – is one of the replies to the millions of marriage proposals Alexa had received so far. Thankfully, responsible designers of commercially available conversational AI ensure, that users are always made aware, that these agents are computer systems with no feelings or thoughts. Nevertheless, in line with similar previous research, our study has shown that users still attach feelings, attribute agency and perceive a relationship with conversational AI, which shares similarities with human relationships. We believe that this topic will accompany us for a while and by far we cannot provide a comprehensive answer. But we hope to have shed a bit more light on a better understanding of how humans perceive their relationship with conversational AI and inspire future research to take this perspective into acount.

This is a brief summary of the first research collaboration between scip AG and the Social Processes Lab of the Leibniz Institut für Wissensmedien, which was presented at 5th AAAI/ACM conference on Artificial Intelligence Ethics, and Society (Oxford, August 1-3, 2022)

Our experts will get in contact with you!

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Our experts will get in contact with you!