Human and AI Art

Marisa Tschopp

Gap Between Attitude and Behavior in Human-Machine Interaction

However, this is only part of the picture to better explain the role of trust in human-AI interaction. It may be worthwhile to be more accurate with the witty no trust, no use slogan: The negatively-framed hypothesis implies a positive, congruent trust-use relationship: The more users trust a technology , the more likely they use it, their behavior follows their attitude. However, this rationale fails to address incongruent behavior. No trust, no use is not adequate for explaining other scenarios, for instance, that some people who do not trust a certain technology will still use it. Little do we know what actual reliance behaviors of people with no or low trust attitudes look like. Drawing upon the learnings from privacy researchers on the privacy paradox, we aim to better understand the no trust but use relationship, which can be interpreted as actual reliance behavior not congruent with the respective trust attitude.

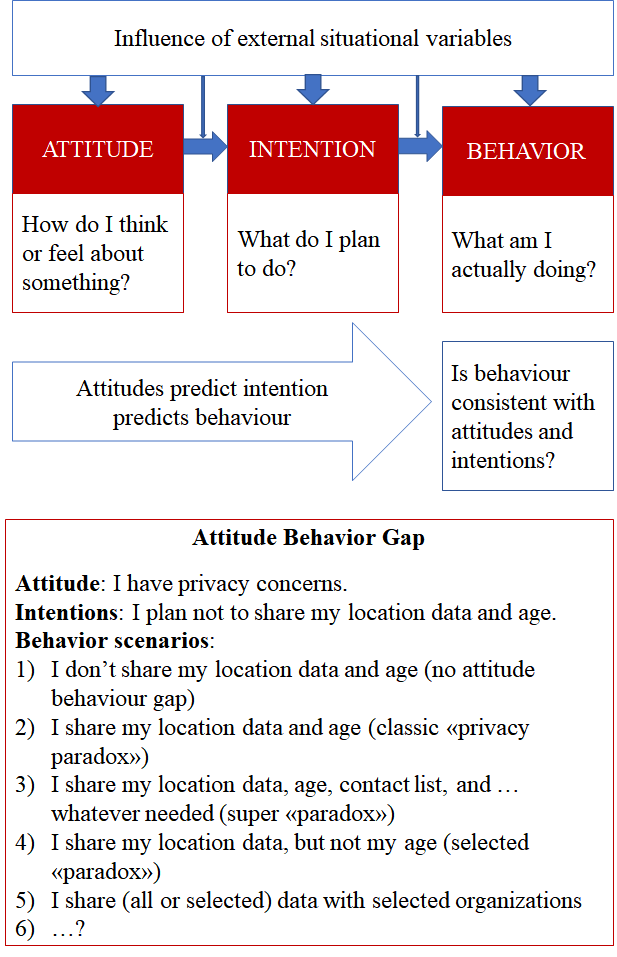

Much of consumer psychology is about consumer choices: Researchers aim to understand how attitudes, values, beliefs or knowledge are formed and how these variables affect consumer behavior. Most people would find it normal, that people who have a certain attitude, would act upon this attitude. However, this is not always the case. The phenomenon, that people behave against their attitudes, is called attitude-behavior gap, and has found particular interest in privacy research. Numerous studies have found, that people’s use of technology is characterized by the so-called privacy paradox (Norberg, 2007): People say they care about privacy or have privacy concerns, but they are careless when it comes to their actual behavior. The figure below shows in a simplified manner, that an attitude is formed, influencing the intention, which then leads to an action.

As seen in the image above, it is important to differentiate between intention and behavior. Although intention is found to be generally a strong predictor of behavior, studies on the privacy paradox have shown that the intention is not accurate enough to explain actual behavior. Unfortunately, intention is mostly studied as an outcome variable as it is much easier and cheaper to operationalize than actual usage variables (Sheeran, 2002. Kokalakis (2015) suggest differentiating privacy concerns (e.g., stalking, secondary use by a third party or improper access by employers) and privacy attitudes (e.g., I care about privacy). Moreover one can differentiate between privacy intention and privacy behavior: Adoption, for instance, purchase or privacy protection behaviors, such as refusing to provide information or providing false information (Son & Kim, 2008).

Most studies focus on social networks and e-commerce, with growing literature on smartphones. Research in the area of smartphone usage often attempts to explain issues related to privacy paradox in the context of the Uses and Gratification Theory (UGT) or the Information Boundary Theory (IBT) (Sutanto 2013). Other avenues of research tackle emotions. In a study conducted shortly after the Facebook scandal involving Cambridge Analytica, Sarabia-Sanchez et al. (2019) find that there is no relationship between the intensity of the reported emotions and the management of privacy setting by the surveyed facebook users. A large portion of research regarding privacy paradox in the digital field addresses cybersecurity. In what they call the intention-behavior gap Jenkins et al. (2021) find that people’s desire to minimize required effort negatively moderate their actual security behavior . In their study of security behavior of smartphone users Das and Kahn (2016) find that the most consistent predictors of security behavior are the perceived efficacy and cost of adopting security responses. Another approach to explaining the privacy paradox in the digital context relates to rational fatalism according to which the level of fatalistic belief about technologies and business impacts the likelihood of users to protect their privacy on the internet in general (Xie et al. 2019).

There is an emerging stream focusing on the privacy paradox in the context of conversational AI. It has been shown that the nature of the technology and the kind of information to be shared (age, weight, income, etc.) makes a difference. Smart speakers are per se intrusive as they share their users’ most private social sphere. Furthermore, GDPR privacy recommendations are only poorly implemented due to the conversational interface (CUI) and thus hard to access (Brüggemeier & Lalone, 2022). Another factor that differentiates conversational AI from other contexts is based on the CASA paradigm (people tend to treat computers as social actors) and anthropomorphism (the tendency of humans to humanize machines). Smart speakers likely create a social presence, for instance, the perception of a companion relationship which has been shown to foster undesirable disclosure of personal information (unintended nudging). These singular characteristics justify an an investigation of the attitude-behavior gap specifically in the context of conversational AI, as conclusions drawn from studies on other technologies cannot be generalized.

Researching the privacy paradox has produced contradicting results. Researchers tried to challenge the privacy paradox in various contexts . One stream of research focused on finding evidence that people’s behavior is consistent with their privacy attitudes and/or intentions, thus, paradoxical behavior was not found (e.g., Young and Quan-Haase, 2013 in social networks; Wakefield, 2013 in e-commerce). The fact mentioned above that privacy behavior is highly contextual, privacy concerns should be differentiated, and that it depends on what kind of information was at dispute, complicates comparability and explains different interpretations of studies. Overall, most of the studies have shortcomings in the methodology. This is a major problem as it questions interpretation and generalizability. This hard problem should have the highest priority for the field to move forward. Surveys and experiments (mostly based on convenience samples) are most used, raising issues of validity and generalizability. The biggest problem might be the reliance on self-reported concerns, attitudes, and intentions.

We believe that digital privacy is a desirable societal value, mirrored by the establishment of the GDPR and promoted by ethicists or so-called privacy activists. It is plausible that individual privacy attitudes and concerns are largely biased due to the phenomena of social desirability. This bias is the tendency of respondents to answer questionnaires in a generally favorable manner. Hence, the question many ask is: How much do people really care about privacy? If you could establish a real measure of privacy attitudes, this would be the shortest way to challenge the existence of the privacy paradox. Since, this is impossible, as with all latent variables, researchers need to be even more creative.

Kehr et al. (2015) suggest that the “social representation about privacy is not yet formed by lay users”. In line with this statement, Barth et al., (2019) found the paradoxical behavior in their experiment (controlling for technical knowledge, financial resources and privacy awareness), however, they could not find a representation of privacy in their respondents’ reviews of the technology used. They conclude, that privacy is not rated important. Furthermore, functionality, design and perceived benefit are more important than privacy.

The EU has developed a framework for trustworthy AI, to foster responsible use of artificial intelligence . They suggest a close relationship between trustworthiness (as properties of AI systems) and the attitude of trust, with privacy being one of the components of trustworthiness. It is plausible, that the learnings from the privacy paradox can be translated (or modified) to a potential trust paradox. A theoretical framework of a trust paradox does not exist and could be developed, for instance, based on the review of the multidimensional approach of privacy and smart speakers by Lutz and Newlands (2020). Taking into account the above points, a trust paradox is likely to be context-sensitive (which is why we focus only on conversational AI), with the variables to be theorized from relevant trust literature compared to the privacy research. The role of knowledge, financial resources as found in the article by Barth et al. in the IOT context (2019) could be highly relevant, for example. What may be specifically important is to integrate the different actors that play a role in the trust framework: The actual smart speaker (Alexa) versus the company behind it (Amazon), and other third parties that may play a role (e.g., Philips smart light bulbs or NHS in the UK giving health advice over Alexa). Looking at the variety of explanations of paradoxical behavior in the privacy context, it is plausible that the interpretations for a trust paradox are similar. Based on the privacy paradox literature, interpretations can be similar, except for the social theory interpretation, which probably only occurs in social networks (e.g., disclose personal information to maintain their online lives).

Investigating a potential trust paradox will face the same methodological challenges as stated above, like self-report measurement and lack of detail, for instance, differentiating trust concerns and trust attitude. Trust may even be more difficult, as various measures exist and in opposition to privacy, there is no official law or anything comparable that could serve as a threshold to what ‘adequate’ trust is and what not. The EU Guidelines for trustworthy AI may serve as theoretical background. There is a high danger of recreating the same problems if methods are not chosen creatively and simply focus on the intention to use. On the other hand, investigating intention to use may serve well as a pilot study and might be good enough due to the novelty of the problem.

Open questions remain: What is the equivalent measure for trust concerns in performance, process and purpose of the conversational AI? What kind of trust awareness is relevant (compared to the relatively clear concept of privacy awareness)? How to operationalize technical knowledge in the context of conversational AI? How to integrate the different actors of trust relationships? And, while you can adapt compare the adequacy of individual privacy decisions to existing rules and regulations, what are adequate individual trust decisions?

We believe that the respectable work of privacy researchers is a valuable opportunity to better understand trust in human-AI interaction, more specifically, trust in conversational AI, which is our topic of interest. Research on the privacy paradox has produced contradictory results and faces shortcomings in methodology, thus remaining a wide-open issue with a lack of knowledge specifically in the field of conversational AI (Kokalakis, 2015; Barth et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020; Lutz & Newlands, 2021). However, these challenges also pave way for innovative research agendas. It is plausible, that a trust paradox can be found in human-AI interaction, similar to the privacy paradox, including the tough challenges observed. Trust is a complex construct with cognitive and emotional elements and although we expect to find many similarities to the privacy paradox, we also theorize to find differences to the trust paradox in hope to generate useful recommendations for research and practice.

Finally, the findings regarding the attitude-behavior gap must be separated from the ensuing expectations or the perception individuals have with regards to how the providers of these services should act. Martin (2016) finds that individuals retain strong privacy expectations even after disclosing information, meaning that their willingness to allow e-commerce, social media, smartphone, browser, smart assistants or other service providers gain access to private data does not change their attitude with regards to privacy.

This article was written by Marisa Tschopp and Pierre Rafih. Pierre Rafih is Professor of Investment and Finance, Corporate Management and Controlling at the University of Applied Management, in Ismaning near Munich. His research areas are in Behavioral Finance with a focus on Investor Behavior, Financial Innovation and Financial Literacy. We also want to thank Prof. Dr. Dagmar Monett (HWR Berlin) for valuable discussions on this topic and feedback.

Our experts will get in contact with you!

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Our experts will get in contact with you!