From crisis to opportunity

Michèle Trebo

Think first, then don't!

The term sharenting is made up of the English terms sharing and parenting and describes the phenomenon of parents sharing media online, including photos and videos of their children. If parents publish an excessive amount of details about their children’s lives, this is known as oversharenting. Sharenting can promote family cohesion, capture memories, express pride or help build online communities (not exhaustive). However, it also harbours often neglected and underestimated risks, which this article focuses on. One example of this is a mum fluent who seems to put publicity and money above the well-being of her children. In the SRF report Kinderfotos auf Social Media she explicitly says and is quoted as saying “Ich will nur Gäld verdiene mit chlini Chindä, ja und…welli Mami möchti nid di Hei chöne schaffe und echli Geld verdiene.”

In Switzerland, it is generally permitted to share media such as photos or videos of children, but the right to one’s own image applies. Every person has a right to their own image and can generally decide whether and in what form media in which they are depicted may be recorded and published, including children. Even four-year-olds can communicate whether they want to be recorded and whether they like a medium. Their decision must be respected. Images are relevant under data protection law as soon as people are recognisable in them, including in group photos if it is possible to identify individuals. The extent to which this applies is assessed on a case-by-case basis. The consent of the persons depicted is required if there is no other justification. There are exceptions in cases of overriding public or private interest, such as reporting on significant events. For the use of archive images, the identity of those depicted must be established and their consent obtained. Consent must be based on “appropriate information” and be given “voluntarily”. In the case of group photos, a general note is sufficient, whereas in the case of individual photos, individual consent is required after viewing the photos. In the case of public photographs, the inclusion of passers-by is deemed to be incidental as long as there is the option to delete the images or refrain from publishing them upon request. On 16 November 2022, the Federal Council took a position on a submitted text dealing with children’s right to privacy and the protection of their personal rights, which are often violated by the actions of parents and guardians. According to this text, parents often do not realise that actions such as sharenting can affect their children’s privacy. The Jugend und Medien platform provides information on this topic, but there are concerns that this information is not sufficiently disseminated and that children’s rights are still not sufficiently respected. In its opinion, the Federal Council states that the existing legal basis, including the Federal Constitution and the Civil Code, is sufficient to protect the personal rights and privacy of children. Parents have a legal obligation to protect the welfare of their children and the child protection authority can intervene if the limits are exceeded. Parents and guardians are already sufficiently sensitised to the protection of their children’s privacy through the involvement of various organisations and initiatives at federal level, such as data protection and public information officers and child protection organisations. The Federal Council does not consider it necessary to expand the Jugend und Medien platform or to introduce a new campaign to raise awareness among adults, as there are already numerous resources and initiatives in this area.

The legal consequences of unauthorised publication of children’s media can be serious. Sharing such media without the required consent can lead to claims for damages. In some countries, there is also the threat of fines or even imprisonment. In particularly serious cases, if the sharing of media is deemed to be part of abuse or neglect, parents may be deprived of custody. There are several cases in Switzerland in which the Child and Adult Protection Authority (KESB) has intervened after it was established that parents were being careless and selfish with online data protection. The careless publication of sensitive data or media online can be an indication that the child’s welfare is not being adequately protected. Such incidents often lead to the KESB taking a closer look at the family environment to ensure that the children grow up in a safe and supportive environment. Data breaches can be seen as part of a wider pattern of negligence or irresponsibility. An 18-year-old woman from Carinthia in Austria sued her parents because they had published photos of her on Facebook in 2009 without her consent. The parents refused to remove the 500 or so photos, whereupon the woman took legal action after reaching the age of majority. Her father insists that, as the author of the photos, he has the right to publish them. Under data protection law, the parents face a fine of up to 10,000 euros. In France, for example, there is no specific prohibition against the publication of children’s media. However, as soon as they reach the age of majority, children have the right to sue their parents for invasion of privacy. In such a legal case, they could face fines of up to 50,000 francs or even a year in prison.

Sharenting can harbour considerable dangers. A survey by SRF (Swiss Radio and Television) shows that many parents are aware of the risks, yet these are often underestimated. By sharing media and details of their children’s everyday lives, parents largely relinquish control over these media and information. One of the most serious risks is the use of even seemingly harmless images or videos for inappropriate purposes, including paedophilia. Media can be misused in this context, for example by using special tools to search for specific characteristics (e.g. “boy, blonde”) and disseminate them. Parents who post such media online are unwittingly providing material that can be used in criminal circles. There is also the risk of cyberbullying, when a child’s personal information or embarrassing media is used by peers to tease or bully the child in question. Sextortion, blackmail with real or manipulated media, is another threat that can arise from the careless use of digital media. Another risk is cybergrooming. Publicly accessible media, such as club photos of a football club, which are not only accessible to club members and often contain information such as training times and locations, can be misused by criminals as a catalogue for picking out children. Although this is a rare occurrence according to SRF, it poses a serious threat. The ongoing development of artificial intelligence (AI) is exacerbating this problem. AI can be used to create contexts from images that show the child in situations that never took place. This can damage the child’s reputation and have long-term consequences for their digital identity. Even in communicative platforms such as WhatsApp, where media and messages are shared in group chats by families, for example, parents lose control over the distribution of their children’s media. These can easily be forwarded and used outside of the originally intended context. According to a recent study involving 1600 parents, half of those surveyed regularly post pictures of their children online, while the other half do not. One in ten parents surveyed share images on a weekly or monthly basis. More than 20% of parents with children older than three do not ask their children for permission before posting their pictures online. Children themselves have different opinions about sharing: Some are indifferent, while others are uncomfortable. According to one estimate, the average 13-year-old child has around 1,300 images of themselves online, which illustrates the scale of potential digital exposure.

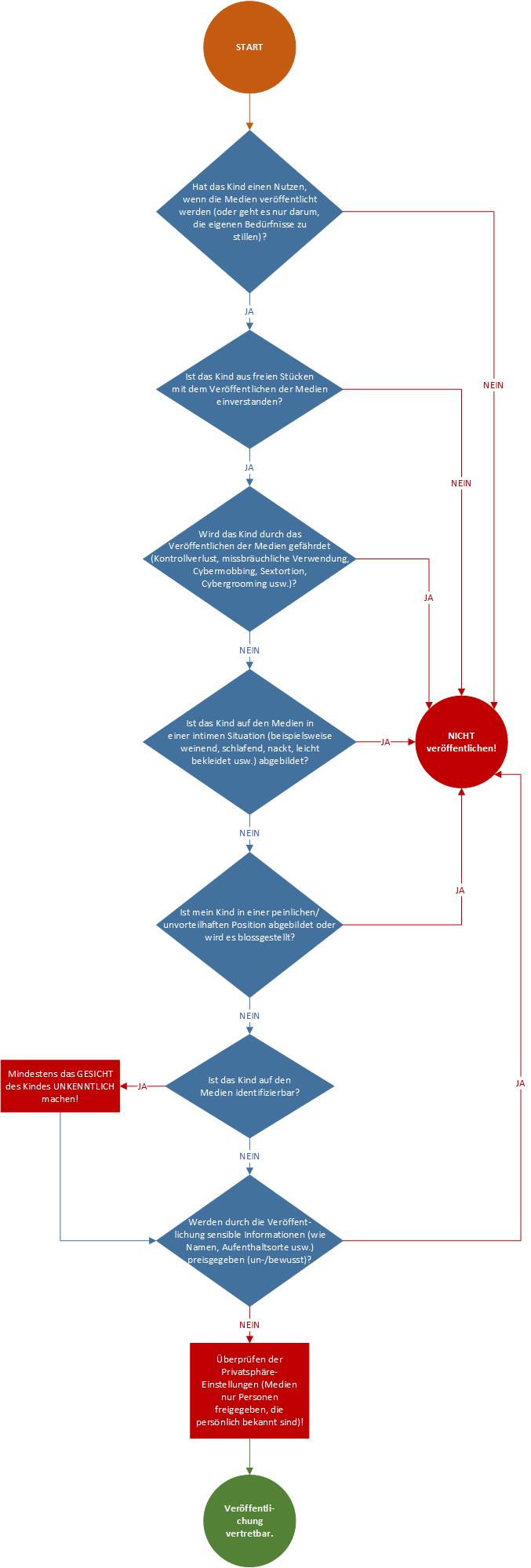

We generally advise against publishing media that depict children. If you still want to publish such media, you should at least give the thoughts shown in the diagram some thought and scrutinise yourself critically.

First of all, you should ask yourself whether publishing the media is in the best interests of the child or rather serves your own fulfilment. There is usually a narcissistic motive behind the publication of children’s media. Another important point is to ask the child concerned whether he or she agrees to the publication of the media in question. If the child does not want the media to be published, this decision must be respected. If, for example, the publication of the media would jeopardise the child’s welfare, if the child is in an intimate or embarrassing situation on the media or if sensitive information is visible, publication should be avoided. If the child is identifiable on the media, the risk can be reduced by at least making the child’s face unrecognisable.

There are two common methods for making a face unrecognisable in an image: Pixelating and covering with an emoji. However, caution is advised, as these techniques are not infallible. Both methods reduce the amount of visible data and, in principle, cause irreversible data loss. This means that the original image information behind the pixelation or emoji is no longer directly accessible. Technically, it is extremely difficult to completely undo a pixelation or remove an emoji in order to restore the original image underneath. The existing methods of reconstruction are based on interpolation or estimation of information, which is an attempt to reconstruct the missing or obscured parts of the image based on the available data. These methods can at best provide an approximation to the original image, but cannot reproduce the exact original. However, depending on the quality of the original images and the technique used, this may be sufficient to make the identity of a person recognisable.

Sharenting has both positive aspects, such as capturing memories and forming online communities, as well as numerous risks. The dangers include the possible use of media for inappropriate purposes such as paedophilia, cyberbullying and cybergrooming. Many parents ignore the dangers. In legal terms, the sharing of media depicting children is permitted in Switzerland as long as the right to one’s own image is respected. This right requires the consent of the person depicted, which can and should be obtained from pre-school children. Breaches of privacy can have legal consequences, including possible legal action or penalties. It is advisable to avoid sharing images of children as a matter of principle or at least to carefully consider which media are published, always prioritising the child’s welfare. The use of facial obscuring techniques such as pixelation or covering with emojis is one way to minimise the risks, although these techniques do not guarantee that the original data cannot be fully restored. As a general rule, children’s media does not belong online!

Our experts will get in contact with you!

Michèle Trebo

Michèle Trebo

Michèle Trebo

Michèle Trebo

Our experts will get in contact with you!