You want more?

Further articles available here

How do you generate trust for your A.I. solution?

In the AI context, there are various reasons, why trust has become a very popular research topic. For example, when lives can be saved in the military context, where robots are designed to replace humans in high-risk situations (Yagoda and Gillan, 2012). Or in everyday life, when it comes to self-driving vehicles. Trust has always played a big role in the adoption of new markets, technologies or products, like e-commerce, the fax or mobile phones. It will continue its impact on business and economic behavior, for instance, if you consider the use of digital assistants like Alexa to shop for food.

What makes the subject of trust in the AI context so appealing and how is it distinguished from other innovations? One reason stated by Siau and Wang (2018) is that, compared to other technologies, there is a lack of clear definition of processes, performance and especially the purpose of the AI, with respect to the intentions of its provider. Furthermore, open questions regarding ethical standards, the notion of dual-use research, lack of regulations and questionable data privacy as well as the uncontested supremacy of the tech-giants, leave a bad taste behind. Companies start AI-Washing their products and processes or using robots and holograms simply to pep up their marketing. The problem is that there is a fine line between being an innovator and early adopter and making a fool out of yourself by using AI (or pretend to use AI) just to be part of the club and create some media buzz. This should make it pretty clear that this is a bad foundation to build and maintain trust upon.

Although there may be clear benefits for humanity, like defeating cancer or halting climate change, AI is often viewed with great skepticism as the hype around AI leads to justified resistance. Thankfully, because trust is inflating nowadays, people tend to trust too fast und unreflectedly, when it comes to data for instance (Botsman, 2017). We should step back here and ask the same old question all over again: Whom do we trust?

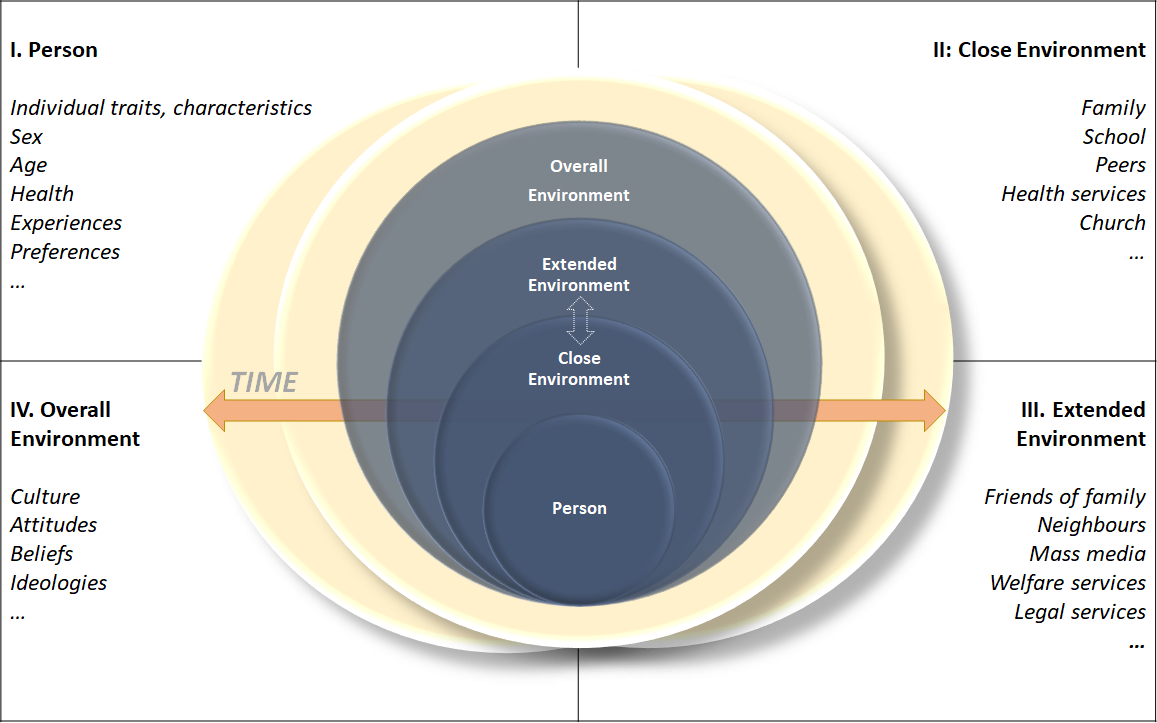

Exploring the nature of trust from a systemic perspective in the context of this technology is quite an effortful endeavor if done systematically. This report tries to integrate the most important aspects and perspectives to gain a bigger picture. For this reason, the framework of this analysis is inspired by the Ecological Systems Theory by Bronfenbrenner (2009). Furthermore, unnecessary complexity is reduced, wherever possible, for example, changing the nomenclature into more intuitive terms like Overall Environment instead of Exosystem. The figure below shows the various levels from the individual person to the national culture, integrating also historical classification. Notably, this review does not strive for completeness, but is rather of explorative character to exemplify the manifold opportunities and research questions one can ask.

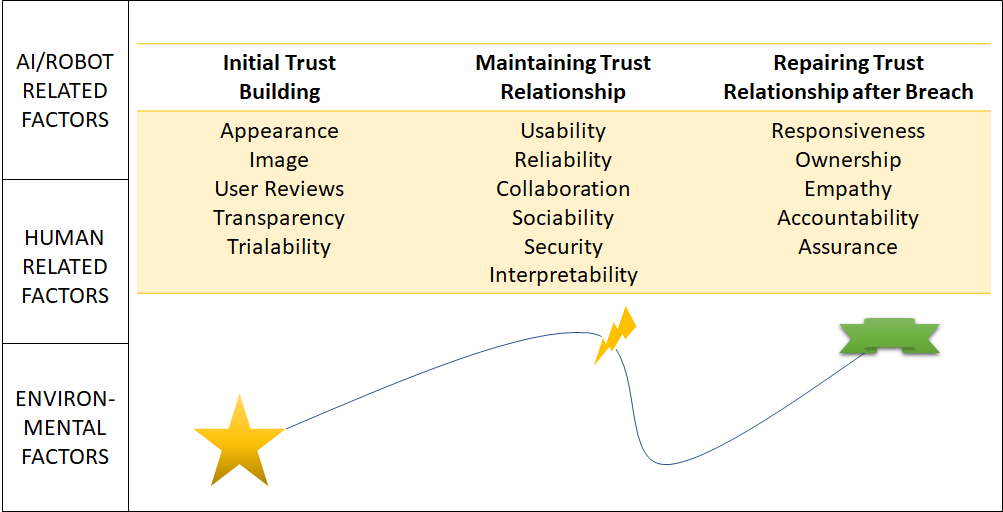

In general, trust is a term associated with dynamic and stable properties, with a wide array of research questions and interrelated terms. The focus can be put on rather static attributes of personal trust factors or on a more dynamic perspective, where trust is perceived as a process – from building, maintaining, and developing trust as well as destroying and regaining trust. Situational factors from time to culture or organizational structures, have to be bared in mind when exploring moderating effects. A popular, rather market-driven focus is the exploration of trust building conditions (socalled antecedents of trust) as well as characteristics of one-on-one trust relationships.

To put it in a nutshell, questions and definitions can look at an individual, a relationship, a situation and/ or a process.

The vast array of interrelated terms, that may influence the outcome, is on top of the complex topic of trust: the role of control, education and knowledge, bias and perception errors, properties of interaction, calculus-based trust, reduction of complexity, consequences of trust breaches, risk, past experience, future expectations, vulnerability, bounded rationality, expectation management, instability/insecurity of the ecosystem,…and most likely many more. Associated terms in human relationships are integrity, honesty, benevolence, and authenticity, whereas, in human-computer interaction concepts of competence, capability and reliability are of vital importance when it comes to trust in a system or a robot. Furthermore, the provider of the technology has a strong impact on the human-technology-trust relationship, too. This refers mainly to the brand image, especially with regards to the perceived benevolent and authentic purpose of the company. This is why many tech companies focus on their ethical mission statements now (Botsmann, 2017; Hancock et al, 2012; Hengstler et al, 2015; Siau and Wang, 2018; Ullmann and Malle, 2018).

On the individual level, research questions focus on the trustee as a person and its rather stable biological and psychological characteristics. There is a long tradition in psychological studies to explore trust as a stable personality trait, combining it with other personality scales like the Big Five Personality Scale. These studies are looking for correlations to other traits like openness or extraversion and can be used as a pre-assessment in recruiting if the recruit is suitable to work in a human-robot team. Studies in the field of Human Robotics Interaction (HRI) have yielded no significant results when looking at the personality of a trustee to trust a robot. A study by Billings et al. (2012) in the military field showed, that the human-related factors (as well as environmental-related factors) only had a small to moderate effect on building trust in a robot.

In a meta-analysis of antecedents of trust, the researchers found out that robot characteristics seem to have the strongest effect on trust building: this includes the performance, appearance, and other characteristics of the robot. To measure trust, the researchers used various scales, for example the Interpersonal Trust Scale (by Forbes & Roger, 1999 in Billings et al., 2011) or the NARS which measures negative attitudes towards HRI. Current research is on the edge of validating trust scales in Human-Computer-Interaction, but further research has to be done (Yagoda and Douglas, 2009; Ullmann and Malle, 2018).

The close environment looks at the role of the closer, situational factors, which can be seen as a team-level approach in the organizational context. From a societal view, it can be interesting to take a critical look at the role of the family or the education in school regarding AI. China is already making concrete plans to implement AI in primary and secondary education, covering topics such as history and applications. Due to early exposure and deeper understanding of AI, it may be trusted and hence adopted earlier and more persistently, in hope for economic and societal benefits (and not only for the sake of winning the AI race against the US).

Leadership studies may also be placed here, measuring the impact of leadership behavior on employees’ trust in AI. More explorative research is needed on how to lead when introducing AI as a tool in a company or in the military when robots are part of a team, as well as comparative studies with regards to digital leadership per se.

Probably the most important factor on this level is the role of media coverage and depiction of AI. What is the current mood regarding AI in the media in terms of hype versus AI-Winter and how does it affect adoption? What is depicted in Science-Fiction movies and how does it influence Human – AI – Interaction? Explorative, grounded-theory approaches using thick, qualitative data, combined with quantitative economic data, for example, may be a good way to depict, understand and predict trust behavior in this context.

This level investigates cultural factors influencing trust in AI, and much more comparative cultural research must be done. However, we can expect to see more of this in the future, since this is a rather methodical approach from the social sciences, who are more and more integrated into AI research. As an example, this can be done by looking at the differences between collectivistic and individualistic cultures and its correlation with trust in AI. An important question to be investigated is the effect of political decisions on the collective trust in AI in a specific cultural environment. Concretely you can ask, what effect the political AI agenda stated by the European Union has on research and practice. Here is an excerpt from their press release, which included the following goals:

Facilitating multi-stakeholder dialogue on how to advance AI innovation to increase trust and adoption and to inform future policy discussions is a commitment made as part of the recent G7’s Charlevoix Common Vision for the Future of Artificial Intelligence.

This perspective takes into account the time dimension, where the historical standpoint is to be taken into account. What is different from the AI and trust studies 15 to 60 years ago? Technology has developed rapidly, but how did trust in technology develop? What longitudinal studies make sense in this context and from what perspective and towards which technology or technology provider?

To sum up, this systemic approach can be used in various ways:

Next, to the various overall perspectives, it is important to be clear of the different actors within the human-computer trust relationship. There is, of course, the trustor and the trustee, the computer to be trusted. First of all, it is important to be clear about what kind of AI in which context we are talking about. Are we talking about an autonomous car in a high-risk situation or are we talking about a digital assistant making an appointment at the hairdresser? Are we talking about a bodiless program making market decisions or a robot employed as a team member in war zones? The characteristics of the actors play an important role, hence it is necessary to understand and define the actors beforehand.

The big tech-companies will most likely play a key role from now. Hype, monopolism, and complexity are the steady companions of the AI era, which calls out for disputing publicly the responsibilities of the tech giants and its products, as well as the rules and regulations they should adhere to in consequence (compare Banavar, 2016).

This discussion is inevitable. Because, in fact, it is not even clear, if actors have a freedom of choice to trust AI or not. It is rather the case, that humanity is moving towards a forced-trust relationship with AI, which consequently creates strong resistance and skepticism. (Luckily!)

Even though much has been done to investigate trust and AI recently, there are many more research questions to answer and scales to validate. Clearly, one cannot investigate all parts in one study. The following graphic based on Botsman (2018), Siau & Wang (2018) and Sanders et al. (2015), suggests possible research areas to focus on, step-by-step, to bring the pieces together. For companies wanting to investigate and assess the AI opportunities, it is worthwhile to investigate these pieces step-by-step the same way, before implementing an AI and further, keep evaluating it continuously (time dimension). From the initial trust formation and antecedents to repairing a trust relationship once it is broken.

The scope of AI in research and practice has to be clear and precise:

This form of situational analysis is a critical success factor, when implementing AI solutions. These questions must be defined and depicted to address and inform all parties concerned to reduce resistance.

The Titanium Research Team has developed a crowd-based Vulnerability Database, which documents vulnerabilities and exploits since 1970. Just recently, an Alexa Skill was developed to further make usability more efficient (Amazon’s digital assistant). Being unsure whether users will adopt the use of a digital assistant, the team, like many others in the field, were wondering how to improve trust in this Alexa Skill, so that users are more likely to use this technology. Having explored the topic of trust and defined the scope of the research project, the goal was to demonstrate, compare and track the capabilities of digital agents, all with the end goal in mind: to increase user trust and increase the probability of this solution being used.

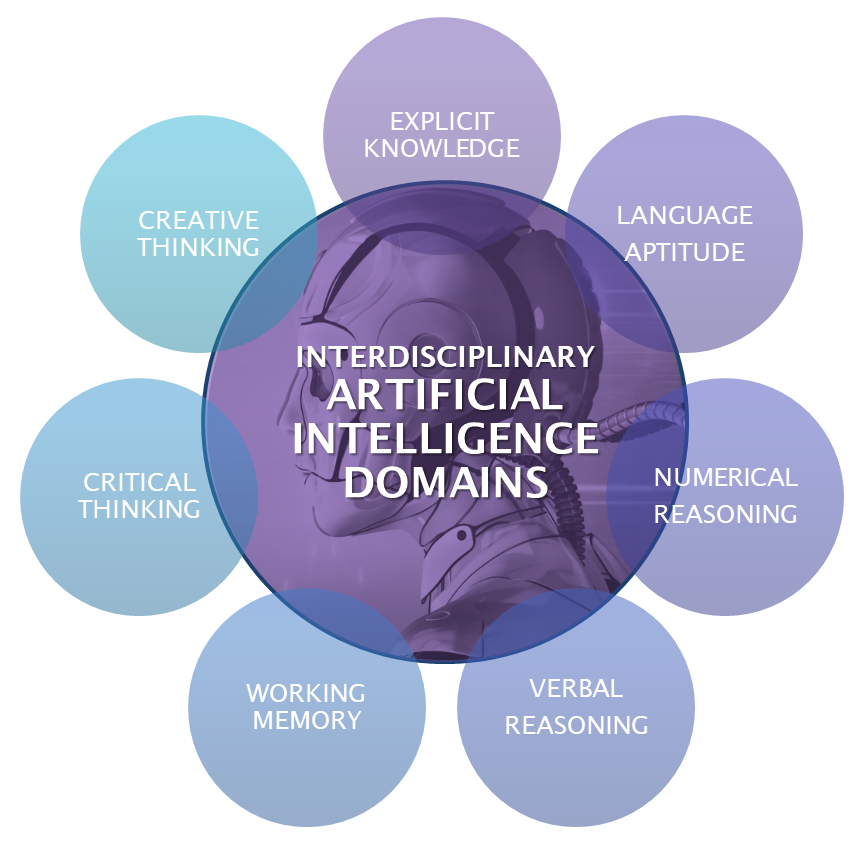

Based on the empirical evidence of how important competence and reliability is, the team has created an A-IQ, an artificial intelligent quotient, as a method to explore an AI’s level of competence. It mirrors the human IQ testing procedures in order to measure, compare between assitants, and track the capabilities over time. Further, from the developer perspective, also to improve the system by finding weaknesses.

From an interdisciplinary perspective, we created the iAIQS – a scale with over 60 items and multilevel evaluation categories to test capabilities and even compare them to human intelligence. The theoretical framework for the test is based on the following AI Domains: Explicit Knowledge, Language Aptitude, Verbal and Numerical Reasoning, Creative and Critical Thinking as well as Working Memory. The test is constructed for digital assistants, chatbots and other speech-operated systems.

Personal digital assistants are designed to help, support and assist humans in various tasks with varying complexity. A natural handling and interaction through speech is vital in order to benefit from the opportunities that AI has to offer. The rationale for adapting human intelligence tests to machines, is to foster and improve this interaction. The A-IQ serves as a trust stamp or mark, as it wants to objectively measure and prove the competence of the digital assistant (compare Finkel, 2018).

This research project aims to trigger interdisciplinary exchange and conversation as well as deeper understanding and benefits of AI based systems. It is based on solid academic research focusing on practical, applicable solutions. The next lab will outline the theoretical framework and methodology and will explain the results of the pilot study, where Alexa, Siri, Google Now and Cortana were tested.

R. Billings, Deborah & E. Schaefer, Kristin & Chen, Jessie & Hancock, Peter. (2012). Human-robot interaction: Developing trust in robots. In: HRI ’12 Proceedings of the seventh annual ACM/IEEE international conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Pages 109-110

Botsman, R. (2017). Who Can You Trust?: Who can you trust?: How technology brought us together – and why it could drive us apart. London: Portfolio Penguin.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (Ed.). (2009). Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hancock, P.A., Billings, D.R., Schaefer, K. E., Chen, J.Y.C., de Visser, E.J., and Parasuraman, R. (2011). A meta-analysis of factors affecting trust in human-robot interaction. In: Human Factors 53 ,5, 517-527.

Hengstler, M.; Enkel, M. Duelli, S. (2016). Applied artificial intelligence and trust—The case of autonomous vehicles and medical assistance devices. In: Technological Forecasting and Social Change 105, S. 105–120.

Sanders, T. L., Volante, W., Stowers, K., Kessler, T., Gabracht, K., Harpold, B. (2015). The Influence of Robot Form on Trust. In: Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 59 (1), Pages 1510–1514.

Siau, K., Wang, W. (2018). Building Trust in Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Robotics. In: CUTTER BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY JOURNAL (31), S. 47–53.

Ullman, D., Malle, B. F. (2018). What Does it Mean to Trust a Robot? What Does it Mean to Trust a Robot?: Steps Toward a Multidimensional Measure of Trust. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Pages 263-264.

Yagoda, R. E., Gillan, D. J. (2012). You Want Me to Trust a ROBOT? The Development of a Human-Robot Interaction Trust Scale. In: International Journal of Social Robotics, 4(3), 235–248.

Our experts will get in contact with you!

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Marisa Tschopp

Our experts will get in contact with you!