Security Testing

Tomaso Vasella

How to Handle your Risks

The term risk appears frequently in general language, yet it is used and interpreted in quite different ways. In the context of information security, the term risk is used according to the following paradigm: A risk is a circumstance or a factor that can impair the desired functions or properties of an object or cause them to be no longer available. In the context of information security risk management, the objects are usually called assets. They represent what needs to be protected or what an individual risk relates to. An asset can be a company, a department, a process, a computer system, an application, etc. For example, a web application could be the asset and the desired properties could be its performance, reliability, correctness of data processing and protection of confidential content. Risks cannot exist on their own, they always refer to assets.

To grasp the relationship between assets and related risks in more detail, two additional terms are used: Threat and vulnerability. Assets are never perfect: An application may contain errors (bugs), a process may fail, a computer system may have insecure access controls, etc. Such characteristics of assets are called vulnerabilities. A vulnerable asset does not necessarily pose a problem, but a problem may materialize if vulnerabilities are exposed to a threat and are being exploited by it.

The notion of risk is thus derived from an asset (an object worth protecting) by considering what threats are relevant to it, what vulnerabilities it may contain, and how bad it would be if they were exploited. This shows two other important concepts: The probability that an event will occur and the impact (the extent of damage) from that event. These two parameters together ultimately yield the magnitude of the risk. Simply put, what can happen, how bad is it, and how likely is it to actually happen?

The following sections go into more detail about these elements and outline a possible approach to risk assessment.

For all considerations in risk management, it must be defined what they refer to. Thus, a scope must be defined, which contains the sum of the assets. The scope can be freely chosen however it seems useful in the specific case. It could contain the information security of an entire organization or refer to parts of it, or it can include only individual systems or a single project. Care should be taken not to omit or forget significant areas. For practical reasons, it may be useful to use several different scopes managed by different organizational areas and to consolidate the corresponding risk management in one central place.

Within the defined scope, the individual assets are defined. These can also be freely defined, but it is worth to think of a meaningful granularity. An asset can be something concrete, tangible such as a system or an application, but also an individual function or a single process. Because assets will subsequently be correlated to threats, risks, and countermeasures it is worth considering how granular risks shall be managed when defining the number of assets whereby particularly risk reporting, communications and the assignment of risks and measures to owners are important.

The next step is to consider which threats are really relevant to the assets. Generic lists of threats exist such as force majeure, unintended errors, etc. that can be helpful as a starting point. When considering threats, it is important to focus on the actual assets and to be realistic. For example, if an asset is a web application, cyberattacks from the Internet are a realistic threat. On the other hand, while earthquakes are always a threat, they are not directly relevant for the web application (but they are for a data center).

Assets may have vulnerabilities that could be exploited by threats. On the one hand, vulnerabilities can actually exist, for example a known vulnerability in a product or an insecure process. In addition, realistically possible vulnerabilities are considered without knowing know for sure whether they currently exist or will exist in the future. Staying with the example of the web application: It is quite possible that it is vulnerable to common attacks such as cross-site scripting, CSRF or SQL injection, but this is not necessarily known for sure without testing. Another example is the realistic assumption that if a login function is present, attackers will try to break into it or possibly misuse otherwise obtained credentials for unauthorized access. Identifying vulnerabilities is often one of the costliest activities in cyber risk management and may require the involvement of external expertise, for example for in-depth expertise or specific testing such as penetration testing.

A vulnerability only becomes a problem if it is exploited by a threat. Therefore, it is necessary to have an idea of how likely this is. This is often not easy, on the one hand because reliable data is often not available, and on the other hand, humans are inherently bad at estimating probabilities. One must therefore proceed pragmatically and remain objective as far as possible. Pseudo justifications such as “nothing will happen to us” or “this only affects others” must be avoided. Estimating probabilities requires expertise about vulnerabilities and threats relevant to the asset under consideration. Probabilities are usually expressed in terms such as “frequently (once a month)” or similar and typically, about four different levels are used.

Here, one asks how bad it would be if a threat actually exploited a vulnerability, for example, an attacker managing to access the data contents of an application or a business application going down for a while. Several dimensions are usually considered, such as financial damage, legal consequences and the impact on reputation. The sum of these dimensions then gives the impact potential, expressed in terms such as “serious” or “minor”, also using four or five different levels. Assessing the business impact requires a good understanding of the relationships between the assets and the business processes that depend on them. It is not uncommon that an impact assessment from a technical IT perspective differs significantly from the impact assessment from a business perspective, therefore good communication among the involved parties is essential.

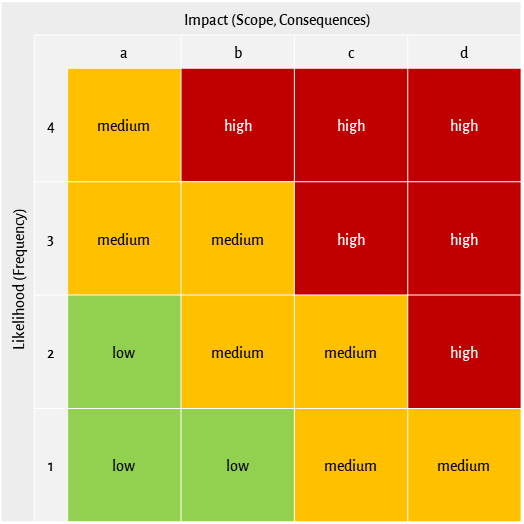

It is evident that something likely with a large impact potential means a high risk, while unlikely events and small impacts mean low risks. This is exactly how risks are rated: The two dimensions impact potential and probability of occurrence (likelihood) are associated, resulting in the qualitative risk rating (e.g., low, medium, high). For this purpose, typically a risk matrix such as the one shown in the following figure is used where the resulting risk rating can be directly determined.

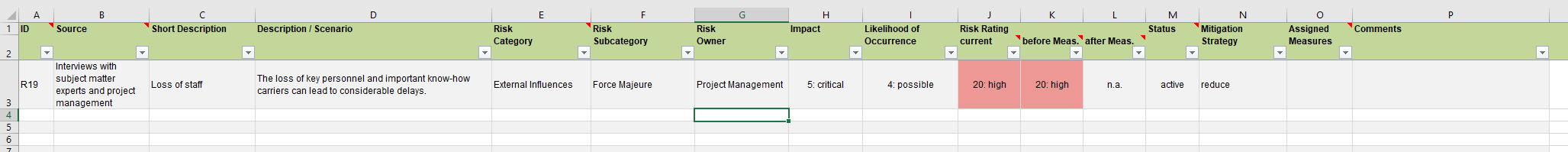

Once the risks have been identified, described, and assessed, responsibilities should be assigned, and the risks should be brought into a form that is as useful as possible for further use. The compilation in a risk register has proven useful, this can be done in a simple form with common tools such as Excel or already existing applications can be used. Care should be taken to support the subsequent processes and in particular the risk treatment as well as possible. A simple example is shown below.

Addressing risks is referred to as risk treatment. Possibilities are risk reduction by taking measures, risk acceptance (one lives with it), transfer (e.g., by concluding an insurance policy) or avoidance, e.g., by abandoning the risky activity. Which approach is most appropriate can only be determined by individual consideration of each risk and of the organizational, regulatory and legal circumstances. Every organization should define a few basic conditions in that respect, including the quantification of acceptable residual risks which is the individual risk appetite.

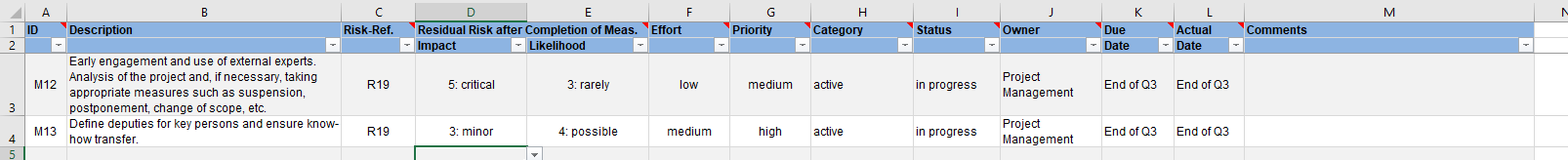

The reduction of existing risks to an acceptable residual risk is achieved by implementing measures or controls, respectively. Measures must be effective, and they should be related to the extent of the risk to be mitigated: The extent of the risk justifies the acceptable effort and the cost of the measure. A risk relates an asset to a vulnerability and a threat and quantifies the potential impact and likelihood. These relationships are often not easily apparent to indirectly involved parties and it is important to communicate the considerations as transparently, clearly, and comprehensibly as possible. This is particularly important in view of the fact that in most organizations, the efforts to manage risks or the costs of measures are approved by a board that was not deeply involved in the details of the risk assessment and evaluation process. Responsibilities must be defined for the measures and an implementation plan with deadlines must be defined. This is usually called risk treatment plan (RTP) and can be as simple as the following example:

The above paragraphs illustrate that the management of information security risks is largely a matter of taking a practical approach. It is worthwhile to use comprehensible, tangible risk scenarios by imagining a real situation and thinking of what could actually happen and how likely it is. Risk scenarios should be described in such a way that they are easy to understand and easy to comprehend even for those not directly involved. In sum, the individual steps are as follows:

Put simply, risk management could be summarized as making conscious decisions. This requires having the necessary data and information, knowing the constraints and boundary conditions, obtaining missing information and, on this basis, weighing the advantages and disadvantages and defining concrete plans for risk treatment.

Much has been published regarding information security risk management and a large amount of information is freely available. A few useful links are:

Our experts will get in contact with you!

Tomaso Vasella

Tomaso Vasella

Tomaso Vasella

Tomaso Vasella

Our experts will get in contact with you!