Security Testing

Tomaso Vasella

This is the new NIST

In 2013, the US President Obama signed Executive Order 13636. This order was intended to increase the performance of critical infrastructures in the domain of cybersecurity risk management. The executive order tasked the US National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) with developing a cybersecurity framework in collaboration with the private sector. This resulted in the well established and widely known NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF), whose initial version 1.0 was published in February 2014. The CSF was designed as a living document that is continuously updated and expanded over time. Version 1.1 was published in April 2018 and deals more comprehensively with the topics of identity management and security in supply chains. In February 2024, Version 2.0 was published as the first major update of the CSF.

This article looks at the main innovations in the current version of the CSF and highlights the most important effects on its practical application.

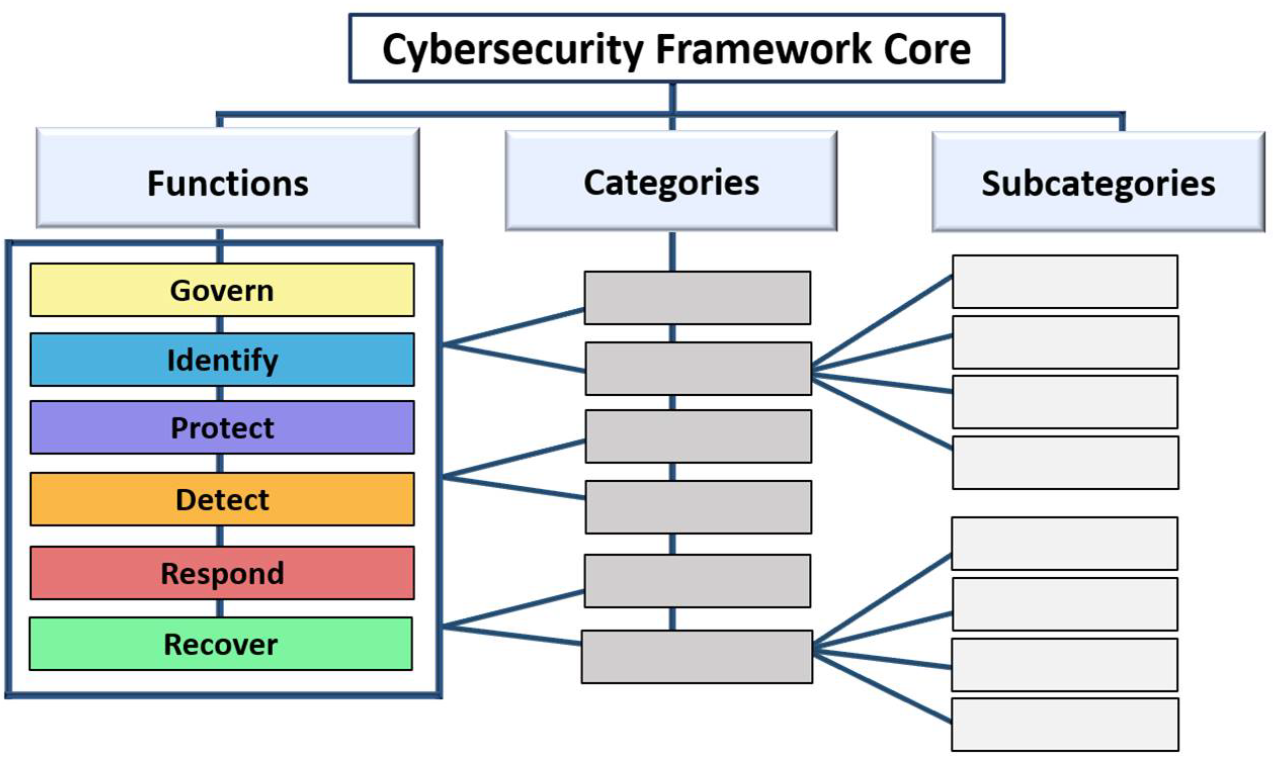

The new version of the CSF also contains the three components Core, Tiers and Profiles.

The CSF Core describes desirable outcomes or security objectives, which are divided into functions, categories and subcategories. The methods by which these objectives are to be achieved are left open and it is the exercise of the users of the CSF to implement suitable controls. This segmentation, familiar from earlier versions, has been retained in the latest version, but a new sixth function Govern (see below) has been added.

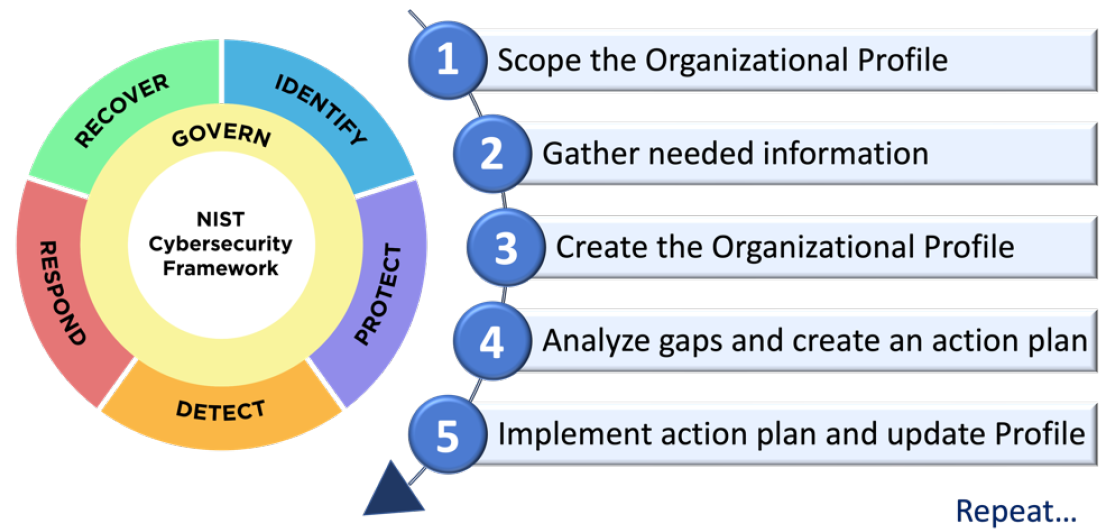

A CSF profile is used to describe the security status of an organization in relation to the security objectives of the CSF Core. Profiles can be used to select and prioritize those CSF categories that appear best suited for a particular organization to achieve its security objectives. Profiles can be used to tailor the CSF to the specific needs of an organization in order to prioritize measures and costs and to develop a plan of action. The profiles can also be used for an actual-target comparison by comparing the security targets currently achieved and those to be achieved in the future in the form of CSF profiles.

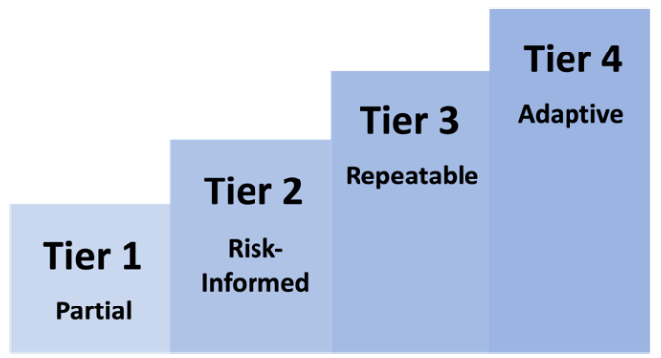

The four tiers – partial, risk-informed, repeatable and adaptive – characterize the rigor and practice of risk management. An organization can determine which tier is appropriate for it based on criteria such as business objectives, risk tolerance and budget.

The CSF version 2.0 includes several significant changes to the scope and area of application. The new framework no longer focuses primarily on critical infrastructures, but extends its scope to all industries, sectors and organizations. Greater attention has also been paid to ensuring that the CSF is relevant and applicable to smaller organizations and those with less advanced security programs. Accordingly, its name has been generalized and it is now simply called the NIST Cybersecurity Framework.

The generalized scope of application is also taken into account with the expansion of the central CSF document to include a series of online resources, which are to be updated regularly (see the section below). The latest version thus has a livelier character than the rather static previous versions, not least thanks to the practical support and examples of implementation.

Probably the most significant structural change is the newly added sixth function Govern. This new function is intended to support CSF practitioners in better integrating cybersecurity risk management into an overarching, comprehensive risk management system for the entire organization. The aim is to anchor the responsibility and accountability for cyber risk management at senior management level, to create a corresponding risk-aware culture and to promote risk communication to management. This emphasis on governance underlines the importance of cyber security as a source of business risk that cannot be considered in isolation and must be regarded on the same level as financial or reputational risks.

In addition, the new CSF expands the measures for supply chain risk management (SCRM) previously included in the Identify function and now also places them in the new Govern function. The CSF emphasizes the essential importance of SCRM in view of the interconnected and complex relationships and dependencies in supply chains.

Similar to previous versions, the CSF contains a description of the functions and the objectives to be pursued. These descriptions can now be found in the introduction and are written in a more practice-oriented language. A short, concise description of the objectives in one sentence is now also found in the functions themselves.

The restructuring emphasizes that the functions of the CSF are not simply linear steps but are interdependent components of a holistic security strategy.

Finally, there is a handy button on the first page of the PDF version with a link to check for new versions of the CSF.

NIST and other organizations have developed various online resources that provide assistance and further information for a better understanding, introduction and implementation of the CSF. Due to the large amount of available information, tools, cross-references and partially overlapping information, it is not easy to gain an overview. The most important resources are listed below.

The so-called Informative References are cross-references that show relationships between the CSF Core and other resources such as standards, guidelines, implementation guidance and others. These resources often contain more practical information than the CSF Core itself and are helpful in understanding how an organization can achieve the outcomes of the CSF Core. Examples of referenced resources are the CIS Controls or the NIST Special Publication 800-218 regarding secure software development. In addition, the Informative References contain Implementation Examples with clear, practical guidance on how to achieve the outcomes of the CSF subcategories.

These references and the implementation examples can be obtained directly as an Excel file. There is also the new reference tool which allows to search for terms in the CSF Core and in the implementation notes. It offers an export option in JSON or Excel format. However, while the exports contain the implementation examples, they don’t contain the cross-references. Nevertheless, the reference tool is a practical way to navigate through the CSF. The reference tool is based on the Cybersecurity and Privacy Reference Tool (CPRT), a more general tool that also contains many references to other NIST standards in addition to the references to the CSF.

In collaboration with the community, the NIST began in 2019 to improve the applicability and interoperability of information security standards by providing a set of informative references. Although they bear the same name as the above-mentioned Informative References, they are not the same resource. They can be looked up and searched in the online reference catalog OLIR (Online Informative Reference Catalog). At the time of writing, OLIR contains four documents for the CSF, including cross-references between the previous and current version of the CSF and cross-references between the CIS Controls and the CSF. Clicking on More Details takes you to an information page about the reference and allows you to generate a comparison report, which can also be exported. The list of cross-references between versions 1.1 and 2.0 of the CSF should prove to be particularly useful as it shows directly where the categories have been moved. The mappings to the CIS controls are also useful and hopefully more will follow.

The Quick Start Guides are individual documents on specific CSF topics. For example, they contain information that helps smaller organizations to start an information security program and there is assistance on the topic of supply chain risk management. The Quick Start Guides themselves have a small manual for a better overview.

The new version of the CSF makes a good impression. In particular, the broader scope of application including suitability for smaller organizations with fewer resources, and the stronger focus on anchoring risk management at the organizational management level are important innovations.

Incorporating supply chain risk management into governance is an important step in the right direction. From a security perspective, supply chains are often unmanageably complex and revent events made it clear that more needs to be done to manage their security on a senior management level.

The efforts to make the framework more practical and dynamic, and the related new online resources help to ensure that the CSF is used as a useful tool rather than a theoretical construct. It can be assumed that the new CSF will be even more widely used and applied than its predecessor and it will be interesting to see what other guidance, practical examples and tools will emerge over time.

Our experts will get in contact with you!

Tomaso Vasella

Tomaso Vasella

Tomaso Vasella

Tomaso Vasella

Our experts will get in contact with you!