Specific Criticism of CVSS4

Marc Ruef

We live in exciting times – particularly when it comes to technology. Many ideas that first sprung from science fiction have now become reality. And it’s amazing how many of those things we now take for granted. The Internet, smartphones and cloud computing have become an integral part of the technocratic information society. The three factors of Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things will exert a decisive influence on the form that technology and society take in the future. This article addresses the current background and future impact that will affect us all.

Over the relatively short lifespan of the information age, we have accrued an enormous quantity of data. Everyone has old devices – smartphones, computers – lying around at home. The data they contain is gathering dust. This data once had a high, direct value. Now it just lies there until we throw the device away. The next generation will take only a bare minimum of its data from devices.

The falling price of hardware and the rising efficiency of software mean that data can be stored easily and cost-effectively. Just 20 years ago, a hard disc with 1 GB cost USD 250. Today, for the same price, you get 8,000 times more storage: 8 TB!

This data doesn’t just accrue in our homes, but also on countless systems on the Internet. On the servers of companies the services of which we use. And on the interim systems, routers and proxies that relay our network communications.

When storage space was still expensive and in short supply, we had to delete old data to make room for the new. Today we hoard it. Sometimes out of laziness. But increasingly because it has a certain value. In fact, many companies make their living from accrued data. In particular, providers that offer free services to their users as commercial data hoarders. And they include big names such as Facebook, Apple and Google.

These companies don’t just store data, they analyze it. The sheer volume of the data that accrues in this way, as well as the methodical analysis it undergoes, is referred to as Big Data. Here, data sets are linked to allow analysts to draw systematic conclusions. In social networks, data correlation lets us see who is friends with whom. Overlapping circles of friends can be identified and potential new friends recommended. And it’s something that functions very well. Sometimes too well; for example, when a psychologist and their patient are recommended to each other. Data is always associated with a certain liability.

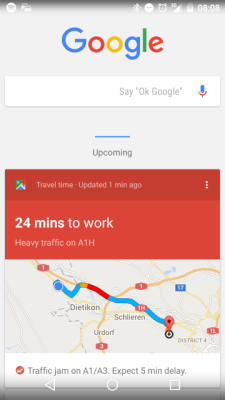

But Big Data can also take completely different forms. For example, Google constantly gathers the position data of all Google users. The Android operating system continuously supplies the current position of the device. The user’s pattern of movement and speed allow conclusions to be drawn about the means of transport in use. And this, in turn, makes it possible to recognize congestion and traffic jams. This is an added value drawn from seemingly insignificant position information.

This capture, correlation and analysis of data presents no great technical challenge. However, the consistent systematization of implementation that is occurring today is phenomenal. When the average speed on heavily used stretches of road falls below 60 km/h, congestion is not far behind. Various map services offer the option of viewing the current traffic flow in real time. Journey times from A to B are calculated dynamically. The slower the average speed, the longer the journey.

Big Data goes a step further when Artificial Intelligence comes into play. The term intelligence has long been contentious – both in traditional psychology and in modern computer sciences. Things are generally perceived as intelligent when they exhibit a certain degree of determination, comprehensibility and efficiency. We call a chess program intelligent when it plays a good game. And we regard speech recognition as intelligent when it understands us with ease. Clearly, there are various forms and effects of intelligence. But when viewed in isolation, the two cited here have little to do with human intelligence as we know it.

Personal assistants are currently working their way into our lives. These forms of Artificial Intelligence (AI), some of them still in a very rudimentary form familiar to us from science fiction films, are meant to make our day-to-day lives more efficient. Google knows where we work and thanks to the accrued location data, it also knows when we generally arrive at our place of work and when we leave again. If it looks like a traffic jam is brewing around home time, the Google Now system informs the user that this will have an impact on their usual routine. In this case, the system recommends leaving work a little earlier in order to get home on time. This recommendation appears at the right time on the device in use – whether it’s a mobile phone or Google’s browser on a desktop PC.

This example illustrates the potential of data correlation that we may perceive as intelligent, but which in truth has a lot more to do with AI; Personal position data is compared with statistical forecasts, resulting in a recommendation. In programming terms, there’s not a lot to it:

if($position == ‘work' && $route == ‘work-home' && $traffic[‘work-home'] == 'jam'){

alert('Leave work early');

}The less transparent the data capture and the complexity of analysis, the more likely we are to attribute a certain degree of intelligence to personal assistants. Google and its affiliates call on well-known mechanisms for their data capture. These include GPS sensors, or the gyroscope in mobile phones. The volume of data points collected from each device multiplied by the sheer number of devices amounts to a very powerful tool.

Interaction with personal assistants contributes to the perception of them as AI. An above-average level of speech recognition, such as that offered by Apple’s Siri, leads to an experience that can seem highly organic. Along with the actual recognition of speech, this requires that associations are also included as content. The AI must be able to understand the content and ascribe attributes to the words.

The next step comes when the AI remembers content from previous conversations or even understands new concepts. But in this respect, today’s personal assistants , as they are offered with smartphones, are far from truly intelligent. They lack the complex logic that an IBM Watson, for example, exhibits. But it is only a matter of time until our future mobile devices can do what a modern supercomputer can do. So it was in the past, so shall it be in the future. 3D storage and quantum computers will start a revolution. But even before then, the computer in your pocket is likely to become the most important instrument of the technocratic society.

Although our devices boast many times the computing power of previous generations, they’re still not strong enough to carry out the kind of analysis associated with Big Data and Artificial Intelligence locally and autonomously. In the current system, speech data is generally recorded and transferred to the provider’s server. The server then analyses the data and supplies a response. This offers the provider yet another means of data capture – retention of speech units. These can assist in the later optimization of recognition, or for additional analysis. The current motto, not just for highly tech-oriented surveillance agencies, is:

If you don’t know what to do with the data, store it just to be on the safe side. You might be able to use it at a later date.

The various providers want to expand their range of services. And this expansion always requires more data. Users, for example, are positively encouraged to reveal as much about themselves as possible, or to use additional services that allow the further consolidation of data. Facebook introduces new data fields with the promise of benefits to the users who complete them. And Apps seek greater access rights in exchange for an improved user experience.

The multitude of various sensors improve the potential of Big Data and our experience with personal assistants. The Internet of Things (IoT) will have considerable influence on these developments. IoT refers to networked devices that at first glance appear atypical, and don’t behave like computers as we know them.

Coffee machines can assess their present volume and tell the owner to restock if required. Coffee producers optimize their revenues, so the coffee drinker is not left high and dry. Heating and ventilation systems can supply weather data, and use it to carry out timely adjustments. Weather services receive better data; homeowners and tenants enjoy reduced heating costs. Wearables can offer information on health influences and effects, so the wearer can seek early medical intervention as problems emerge. And cars can greatly increase efficiency in traffic by exchanging position data and following dynamic routes. The gain for individuals, companies and society would be enormous.

Wearables signal a fusion of human and machine in daily life. It is an effect that is set to greatly increase. To date, wearables has meant electronic variants on existing items of clothing or jewelry. These include watches (Smartwatches), glasses (Google Glass) and rings (Smart Rings). In future, however, there will be support for specific biological processes; for example, by fitting construction workers and soldiers with exoskeletons. Or body-fitted solutions that can be consistently implanted will become widely established. That could mean identification characteristics that replace identity papers and revolutionize payment methods. Or extensions to pacemakers and insulin pumps. These electronic components will open up new potential for continuous data gathering. As well as increasing existing risks, or introducing entirely new risks. The American cryptologist Bruce Schneier refers to the world’s biggest robot, which is currently being built. As such, IoT also has the potential to become the world’s biggest risk.

The combination and fusion of technologies will gather pace. These tech mergers will open up possibilities that are scarcely imaginable today. The idea of today is the product of tomorrow. The classic example is the drone, most of which are now fitted with video cameras. The next step in this area will be the introduction of night-vision devices (residual light amplification and infra-red) and automatic facial recognition. This will allow the development of follow me functions that can deliver a package right to the recipient. Or it could allow the automation of extensive surveillance and tracking functions. The potential of 3D printing is opening up new, cost-efficient and flexible opportunities in these areas and beyond.

At some point personal assistants will have such an overview and will be so sophisticated that they will be able to optimize our daily processes in many ways. And probably better than a real personal assistant could. We expect to see a breakthrough in this area over the next 15 to 20 years. Various areas of work that require highly specialized employees capable of networked thinking will be influenced. In the future, a fusion with robotics will result in the kind of androids we have seen only in science fiction films to date.

The rapid pace of development will increase further and will be met with increasing skepticism from society. There will no longer be widespread resistance to protection of privacy, as we experienced just 20 years ago at all levels of society. However, there will always be individuals and groups who feel their personal rights have been infringed. Purists, keen to reduce technological dependency as much as possible, will become louder. A trend similar to today’s vogue for vegetarian and vegan food will gain acceptability.

Legislators will take notice of these concerns and establish accompanying measures to reduce misuse. Globalization means that we need to aim for international agreements. Law-makers will come under increasing time pressure.

Generations of scientists will have to tackle the moral and ethical aspects that accompany automation. A current example is the behavior of self-driving cars when confronted with a dilemma. If an accident is unavoidable, which damage is easier to justify: the death of a healthy family man or the death of a child diagnosed with a fatal hereditary disease? As soon as human-like robots gain entry into society, the term living being will have to be redefined. This will be associated with a large number of social and legal dependencies. As difficult as it is for us to imagine today, in the distant future people will campaign for the human rights of robots.

At the same time, new technology to protect individuals and their data will hit the market. As is so often the case, it will be a race with an undetermined outcome. And it is questionable if it will ever reach the finishing line.

This race will also have a decisive influence on energy supplies. The numerous devices will require electricity. This has to be generated and distributed. If the prognoses are right, this will require extensive adjustments to the existing infrastructure. The topic of renewable energy, and energy storage, will assume greater significance. The technological and social breakthrough may take some time. But it will be unavoidable and it will reshape the electricity market as we know it.

Also unavoidable will be the rise of the transparent human. Data minimization may delay it, but it can not prevent it. The digital partnership of convenience will last as long as users of Big Data benefit from the symbiosis. And companies are doing everything they can to keep users motivated to collaborate. Health insurers offer discounts when their members share data from their fitness trackers – and that’s just the first step in the commercialization of personal data. Acceptance of the transparent human will mean a loss of privacy. At the same time, it offers the prospect of greater efficiency, insight and opportunity.

The important thing is that the transition is forward-looking, sustainable and fair. It must also be accompanied by a transparent society and transparent state. Only in this way can we prevent the consolidation and abuse of power – the information advantage, in this case. A state that demands the transparency of its citizens while refusing its own transparency naturally arouses suspicion.

Ironically, complete transparency could lead to a situation where shared data has little or no value. Social networks as we know them today may be a thing of the past. Services may need to charge membership fees or introduce enormous amounts of advertising to cover their costs.

This may lead to social segregation, with only the rich retaining complete access to high quality data and analysis. The social problems of inequality, which are ubiquitous today, would then shift to virtual space.

Big Data is concerned with the capture and analysis of data. This should allow conclusions to be drawn that reveal benefits.

Personal assistants will create Artificial Intelligence that will allow interaction with this analysis. The end-user’s experience of this should be as organic as possible.

The increase in sensors means that a huge amount of data can be gathered, leading to an advance in the quality and quantity of analysis. The Internet of Things (IoT) aims to network everyday objects, which will lead to the introduction of a multitude of new sensors.

This improvement will advance at a very fast rate, driven by the combination of new and existing technologies, leading to a degree of social skepticism. Data minimization can delay but not prevent the transparent human. The goal must be a fair transition, which the state must also undergo. The future will bring the greatest opportunity that humanity has ever had within its reach. We can only hope that the right decisions are made.

Our experts will get in contact with you!

Marc Ruef

Marc Ruef

Marc Ruef

Marc Ruef

Our experts will get in contact with you!